Sir Antony Jay

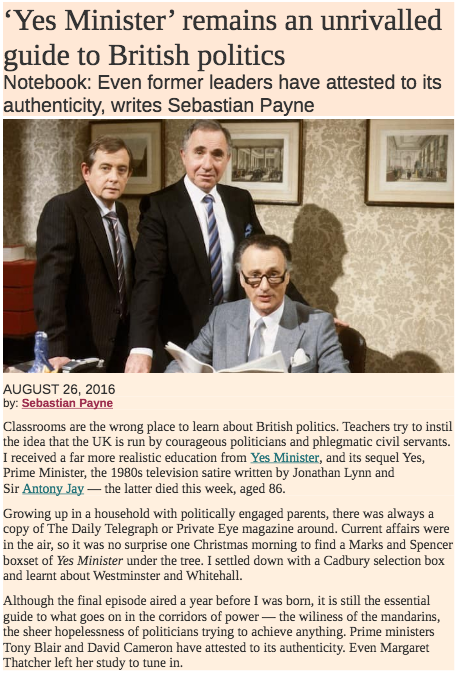

Tony Jay, my collaborator on Yes Minister and Yes Prime Minister died recently. This produced a flood of praise for our work together, like this article in the FT. I'm only sorry he's not here to read it.

I wrote a tribute to him which was shared on Facebook by many thousands of people, and on twitter too. I received a huge response. Here it is. An edited version was published in The Times (London).

Sir Antony Jay

A tribute by Jonathan Lynn

Tony Jay, my writing partner on Yes Minister and Yes Prime Minister, died yesterday. By chance, my wife Rita and I went to visit him on Saturday and saw him before he was taken to the hospital for what turned out to be the last time. He was in pain but when he saw me he smiled and immediately offered me a drink - as he always did. Rita told him that we loved him and he smiled, and then he lapsed into unconsciousness. I am profoundly sad.

Tony was a genuinely original thinker, and a very funny writer. His father, Ernest Jay was a character actor, best known for playing Dennis the Dachshund on Larry The Lamb In Toytown on the BBC’s Home Service and Tony’s first job as a teenager was as an ASM with his father on a Shakespearean theatrical tour during the war. A classicist, he took First at Cambridge, remained fluent in Latin and Greek his whole life, and joined the BBC. As a TV producer, first on Tonight with Cliff Michelmore, and later as Head of BBC Talks and Features Department, his influence was enormous: That Was The Week That Was was produced in his department and later he created the format for David Frost's next show The Frost Report - he planned the first 13 episodes, in which John Cleese, Ronnie Barker and Ronnie Corbett were teamed and all became TV stars as a result.

Almost uniquely, he had a foot in two different worlds: TV news and serious political activity - and show business! He worked on budget speeches and party conference speeches for Geoffrey Howe, Nigel Lawson and Margaret Thatcher, not to add jokes but to help shape and communicate their message, and he received a knighthood after turning around Thatcher’s third and last election campaign with a significant party political broadcast. He produced the Milton Friedman series Free To Choose, and became converted to neo-liberal economics.

I didn’t share his political views and I also feared that these activities would become known while we wrote Yes, Minister and Yes, Prime Minister, which might have given the public the impression that it was a conservative programme. It wasn’t, and fortunately this didn’t happen. Yes, Minister was about government, not politics. Certainly not about party politics. Interestingly, it seemed to reinforce the views of whoever was watching: Tories thought it was a Tory show, Labour voters thought it was Labour. In fact, it was neither - it was, as Rupert Murdoch falsely claimed later about Fox News, fair and balanced.

Tony was a fascinating paradox: though part of the establishment, he remained an iconoclast who was willing to make a joke about almost anything.

On leaving the BBC he wrote two influential books on management, Management and Machiavelli (a big best-seller) and Corporation Man. On The Frost Programme (ITV) he guided David Frost on how to conduct important and difficult interviews, such as the famous one with George Brown, the Foreign Secretary. He edited the first full-length documentary about the Queen and the Royal Family and was intensely proud of the CVO that he was given afterwards. He was a member of the Annan Committee on Broadcasting and drafted the final report which profoundly criticized the BBC.

Then, going into business, he showed himself to be a true entrepreneur. He started the management training film company Video Arts with several partners, including John Cleese. Spotting a gap in the market - he realised that training films, traditionally rather boring, would be much more fun to watch if they showed the audience how not to do a job - he put up the money for the first film himself. The company grew rapidly under his chairmanship and was sold 17 years later for many millions of pounds.

I met him when he started Video Arts: I had known Cleese at Cambridge and he asked me to act in the film for a deferred payment. Never expecting to be paid, I did it for fun and was astonished a few months later to receive the deferment and an offer to act in two more such films. After that, when Cleese withdrew somewhat, to work on Fawlty Towers, Tony asked me write training films, sometimes with him, sometimes just briefed by him. In all, I think I wrote or contributed to about 20 of them.

It was around then that he had the idea for a comedy show about the Civil Service and asked me if I'd like to write it. I wasn't keen at first because I was busy as the Artistic Director of the Cambridge Theatre Company and I needed the income from the training films to support my theatre work. But three years later I was looking for something new to write and we started researching the idea.

We worked together on and off, from the early 1970s until four years ago when illness overtook him. In all that time we never had an angry word. It was, in my opinion, a perfect partnership and it changed my life. He regarded himself as the keeper of Sir Humphrey’s soul, and me as the keeper of Jim Hacker’s. Certain jobs were always left to me: first draft scripts were invariably too long and he couldn’t (or wouldn’t) cut them; smiling, he quoted Pontius Pilate: “I have written what I have written.”

Later, when approached about becoming Chairman of the BBC, he opted instead for retirement to a converted barn in Somerset where his adored wife Jill could have an organic farm.

He gave his polite attention to everyone he met including our sheepdog, named Humphrey because we thought he was sound. He was a loyal, affectionate and very British friend. I have hugged many men over the years but I tried it only once with Tony and he was startled and uncomfortable. Manly handshakes were the right way to express warmth. But he hugged Rita a lot.

I learned more from him than I could ever explain. He was erudite, witty, full of funny thoughts and new ideas, and utterly easy to work with. His death is, for me, the end of an era. For me and Rita it is also the loss of a very dear and loyal friend. We will miss him a lot, and we send our condolences to Jill and their splendid and talented children and grandchildren.